Lunar Dust Could ‘Sandblast’ Astronauts on the Moon, Studies Warn

A new theory of how rockets erode moon soil makes a startling prediction: powered lunar landings may fling around four to 10 times more material than previously thought. The work suggests that without sufficient precautions, rocket-lofted lunar dust would pose a serious sandblasting hazard to cargo and crew on the moon. The physicist behind the new calculations, Phil Metzger, is one of the world’s leading experts on how rocket plumes interact with planetary surfaces. Now that his research has been published in two studies in the journal Icarus, he is calling for more global cooperation on the problem as space agencies plan out long-term lunar infrastructure—including human outposts.

“The amount of damage [that lunar dust] might cause to a spacecraft could be an order of magnitude worse than we believed,” says Metzger, director of the University of Central Florida’s Stephen W. Hawking Center for Microgravity Research and Education. “The international community needs to work on protocols and international agreements so multiple parties can operate on the moon.”

Pulverized into existence by rock-shattering meteoroid impacts, moon dust is nasty stuff. The jagged material can snarl up spacesuits’ joints, clog up radiators, and irritate astronauts’ eyes and lungs—and that’s just the stuff stirred up at low speeds. The moon lacks an atmosphere, so when a rocket lands there, no air slows the material that’s kicked up. Small dust particles accelerated by rocket exhaust can travel many kilometers or even escape the moon entirely.

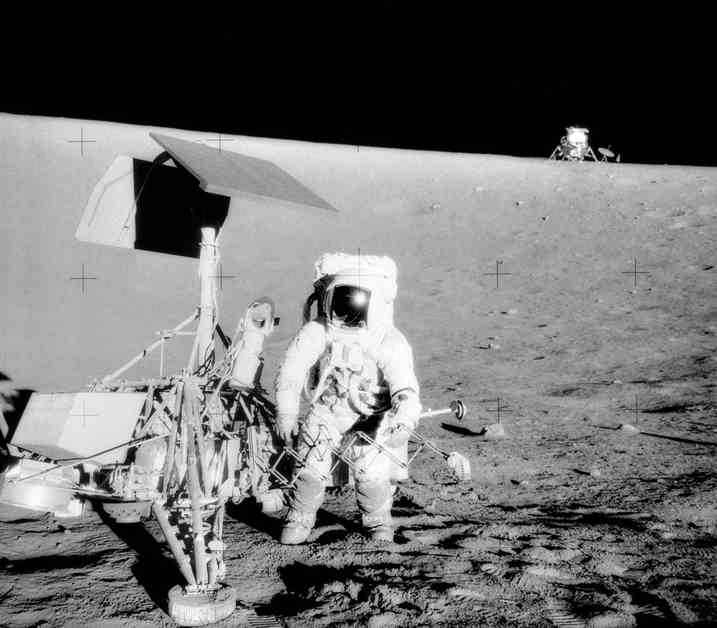

Researchers have known for decades that rocket-flung dust can harm lunar equipment. In November 1969 the Apollo 12 lunar module landed about 160 meters (520 feet) from a NASA robotic probe called Surveyor 3, fulfilling a goal to demonstrate a pinpoint landing. But when Apollo 12 astronauts inspected Surveyor 3, they found that it was caked in dust. Samples of the probe returned to Earth showed severe sandblasting damage, including literal craters.

Concerns around sandblasting have already shaped NASA policy. The agency issued nonbinding guidance in 2011 that recommended small lunar landers should not touch down within two kilometers of the Apollo landing sites to protect the areas from dust. That guidance was co-drafted by Metzger, who worked at NASA at the time, and was based on thousands of simulations. But the two-kilometer cutoff itself was an arbitrary placeholder, to be revisited as the underlying theory of lunar landings improved. The 2011 buffer was just the apparent distance of the lunar horizon from a six-foot-tall person’s point of view.